Say goodbye to more of your privacy!

(Reuters)Raising alarms, Biometric technology is the new trend that dozens of police department nationwide, are gearing up to use. It’s the new iris/facial-scanning device that slides over an iPhone which helps identify a person or track criminal suspects.

(Reuters)Raising alarms, Biometric technology is the new trend that dozens of police department nationwide, are gearing up to use. It’s the new iris/facial-scanning device that slides over an iPhone which helps identify a person or track criminal suspects.

‘Mobile Offender Recognition and Information Systems (MORIS), is made by BI2 Technologies in Plymouth, Massachusetts, is a smartphone based scanner and can be deployed by officers in the field or at the station.

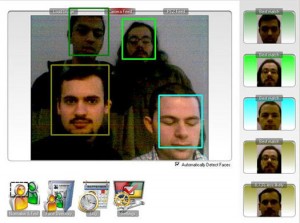

When MORIS is attached to an iPhone, it can scan a person’s face and the image is sent through software at the BI2-managed database of U.S. Criminal records, searching for a match.

According to Bl2, the iris scan is more accurate than other fingerprinting technology used by police, and can reduce the time it takes to identify a suspect.

Some are concerned about possible civil liberties and privacy issues thinking police may randomly scan the population, but Sean Mullins, BI2’s CEO says it would be difficult if not impossible to obtain a clear usable image without a person knowing it because MORIS should be used close up. “It requires a level of cooperation that makes it very overt — a person knows that you’re taking a picture for this purpose.”

That statement is somewhat deceiving or an outright lie depending on your definition of ‘close up’.

According to constitutional rights advocates, the device can accurately scan an individual’s face from up to four or more feet away, potentially without a person’s being aware of it, and before police administer an iris scan, they should have probable cause a crime has been committed.

The blocky device, attaches to the back of an Apple iPhone. To use the iris scan, a police officer holds the phone’s camera about 6 inches from the suspect’s face and snaps a close-up of the eye. The software analyzes over 200 unique features and, if the suspect’s scan is already in a database, an algorithm matches them, and identifies the suspect.

To use facial recognition, the officer snaps a photo from 2 to 5 feet away. Using software from Animetrics, MORIS analyzes over 100 unique features, and compares them to similar scans in the database. There’s also an integrated fingerprint scanner.

Jay Stanley, senior policy analyst with the national ACLU stated, “What we don’t want is for them to become a general surveillance tool, where the police start using them routinely on the general public, collecting biometric information on innocent people.”

The ACLU, concerned about possible civil rights issues, is asking Brockton police, the Plymouth County sheriff and the Massachusetts Sheriffs Association for more information about the new system.

“What kind of pictures will be in this database? Is it the RMV photos? Is it the photos of the prisoners when they are booked? What exactly will this database be?” Laura Rotolo, the ACLU’s staff attorney, said Tuesday.

“We are concerned that they are going to be taking pictures of innocent civilians,” she said.

“Because a system like this has never been deployed by local police departments, there are many questions relating to how its use may impact individual rights,” Rotolo wrote the sheriff in asking for more information about the system.

The MORIS device – with the applications – costs $3,000 – and was made available thanks to part of a $200,000 federal grant funneled through the Massachusetts Sheriffs Association. Some $148,300 of that grant is being used for the system to eventually be used by 28 police departments and 14 sheriff departments in the state.

The ACLU is looking for all documents describing how the program will be funded, a copy of the contract between BI2 technologies and Brockton, Plymouth County or any other entities, and documents that include the description of the databases used the system, including where the information will be sent.

Advocates for MORIS see it as a way to make tools already in use on police cruiser terminals more mobile for cops on the job.

“This is (the technology) stepping out of the cruiser and riding on the officer’s belt, along with his flashlight, his handcuffs, his sidearm or the other myriad tools,” said John Birtwell, spokesman for the Plymouth County Sheriff’s Department in southeastern Massachusetts, one of the first departments to use the devices.

The technology is also employed to maintain security at Plymouth’s 1,650 inmate jail, where it is used to prevent the wrong prisoner from being released.

“There, we have everybody in orange jumpsuits, so everyone looks the same. So, quite literally, the last thing we do before you leave our facility is we compare your iris to our database,”said Birtwell.

Plymouth County Sheriff Joseph D. McDonald Jr. said it isn’t that much different than using fingerprints to identify suspects. “I don’t see a problem with the technology. It is easy to lose sight of the fact that we have been using biometrics for years” with fingerprints.

Police Chief William Conlon earlier said his department will only take pictures of suspects – and will not be snapping shots of average people on the street.

One of the technology’s earliest uses at BI2, starting in 2005, was to help various agencies identify missing children or at-risk adults, like Alzheimer’s patients.

Since then, it has been used to combat identity fraud, and could potentially be used in traffic stops when a driver is without a license, or when people are stopped for questioning at U.S. borders.

Currently “MORIS” is used by the military to identify insurgents.

Facial recognition technology is not without its problems. For example, some U.S. individuals mistakenly have had their driver’s license revoked as a potential fraud. The problem, it turns out, is that they look like another driver and so the technology mistakenly flags them as having fake identification.

Roughly 40 law enforcement units nationwide will soon be using the MORIS, including Arizona’s Pinal County Sheriff’s Office, as well as officers in Hampton City in Virginia and Calhoun County in Alabama.

MORIS costs $3,000, and includes the cost of the smartphone. Together, the two devices weigh 12.5 ounces.

Americans should be concerned about how their driver’s licenses are being used.

A pilot program launched in 2009; the FBI began using facial recognition software to identify fugitives on North Carolina highways. The software measures the biometric features of thousands of motorists’ DMV photos, matching them against mugshots. When the face matches that of a known criminal, the authorities jump into action.

A pilot program launched in 2009; the FBI began using facial recognition software to identify fugitives on North Carolina highways. The software measures the biometric features of thousands of motorists’ DMV photos, matching them against mugshots. When the face matches that of a known criminal, the authorities jump into action.

This technology automatically tracks innocent people, violating the privacy of thousands of motorists.

Federal statutes prevent the FBI from accessing state and local photos like those used for driver’s licenses. However, this program neatly circumvents that federal prohibition by operating out of the North Carolina state DMV.

“Everybody’s participating, essentially, in a virtual lineup by getting a driver’s license,” Christopher Calabrese, an attorney who focuses on privacy issues at the American Civil Liberties Union, told the Associated Press.

FBI officials have organized a panel of authorities to study how best to increase use of the software. It will take at least a year to establish standards for license photos, and there’s no timetable to roll out the program nationally.

Licenses “started as a permission to drive, Now you need them to open a bank account. You need them to be identified everywhere. And suddenly they’re becoming the de facto law enforcement database.”

Gone are the days when states made drivers’ licenses by snapping Polaroid photos and laminating them onto cards without recording copies.

Now states have quality photo machines and rules that prohibit drivers from smiling during the snapshot to improve the accuracy of computer comparisons.

North Carolina’s lab scans an image and, within 10 seconds, compares the likeness with other photos based on an algorithm of factors such as the width of a chin or the structure of cheekbones. The search returns several hundred photos ranked by the similarities.

The system is not always right. Investigators used one DMV photo of an Associated Press reporter to search for a second DMV photo, but the system first returned dozens of other people, including a North Carolina terrorism suspect who had some similar facial features.

The images from the reporter and terror suspect scored a likeness of 72 percent, below the mid-80s that officials consider a solid hit.

Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, questioned whether the facial-recognition systems that were pushed after the Sept. 11 attacks are accurate or even worthwhile.

“We don’t have good photos of terrorists,” Rotenberg said. “Most of the facial-recognition systems today are built on state DMV records because that’s where the good photos are. It’s not where the terrorists are.”

With the success of the program, The FBI will go nationwide if it hasn’t already done so.

1 comment for “Losing Our 4th Amendment”