A short biography of George Washington Carver written by Mary Bagley and posted on Live Science site while factual, omitted what was most important to the Father of Agricultural Chemistry: his faith. Carver, a devout Christian once said that “Without my Savior, I am nothing.”

A short biography of George Washington Carver written by Mary Bagley and posted on Live Science site while factual, omitted what was most important to the Father of Agricultural Chemistry: his faith. Carver, a devout Christian once said that “Without my Savior, I am nothing.”

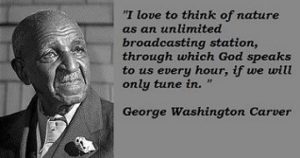

As a scientist, Carver took inspiration from the beauty of creation all around him. He once said, “I love to think of nature as an unlimited broadcasting station, through which God speaks to us every hour, if we will only tune in.”

You have to be someone to get a National Monument named after you, and George Washington Carver was someone – not in his own estimation, but by universal acclaim. Carver sought God’s guidance in all things, and gave God the credit for all his discoveries. Rightly does a National Monument deserve to be named for him, because his story is an inspiration to all Americans. It is one of overcoming odds and serving one’s fellow man, achieving greatness by good works, and devoting oneself to serving others. It is a great American success story for which Americans of all races can justly find inspiration.

Carver’s story is all the more remarkable because of the obstacles he had to overcome. He was born practically a non-person in Civil War times, the nameless son of poor slave parents on a Missouri farm around 1864. His father had been trampled to death by a team of oxen before young George had any memories of him. His mother and sister had been taken by slave raiders in the night, never to be seen again. Barely six months old, the boy and his older brother Jim were adopted by German immigrants, Moses and Susan Carver. The Carvers noticed special aptitudes in him – curiosity, keen observational skills, and love of nature. To this, they added discipline, hard work, and respect for God’s holy book, the Bible. And they gave him a name to live up to: George Washington.

While the Carvers were too poor to give him much more than that, it proved sufficient. At age ten, with a silver dollar and eight pennies in his pocket, Carver walked alone the ten miles to the nearest colored boys school in Neosho where he would sleep in a barn at night and find odd jobs to pay for food and tuition.

Those who know him primarily for his achievements in agricultural science might be surprised to learn that George Washington Carver was a singer, artist, piano player and debater. His spiritual aptitude took root in his fellowship with the YMCA. Throughout his life, he felt the sting of racial prejudice, even witnessing a lynching of another black man by the KKK, but throughout, George remained friendly, open, and diligent in everything he did, rising to the top of his class with high grades and was accepted to Highland University on a scholarship.

Upon arriving at Highland in Kansas, he was in for another major disappointment. Highland University did not realize George was colored. “Young man, I’m afraid there has been a mistake. You failed to inform us you were colored. We do not take colored students here at Highland.” Not giving in to prejudice, Carver worked and saved his money and decided that with God’s help he would find a college that would take him.

At age 26, Carver spent the ten dollars he had saved and traveled to Indianola to entered Simpson College. The rest is history. Though now older than most of the students, and seemingly the only black student, George rapidly excelled and made high grades. He transferred to Iowa State and became the first black man to earn a bachelor’s degree. He was invited to teach, and earned his master’s degree in agriculture in 1896. Carver’s work on plants and plant diseases came to the attention of Booker T. Washington, who founded Tuskegee Institute fifteen years earlier as a place to provide blacks an opportunity for higher education.

Washington offered Carver a position at Tuskegee – “I cannot offer you money, position, or fame. The first two you have. The last, from the place you now occupy, you will no doubt achieve. These things I now ask you to give up. I offer you in their place – work – hard, hard work – the challenge of bringing people from degradation, poverty and waste to full manhood.” Carver accepted.

Upon arriving in Alabama, he was stunned to find he had no lab, no books, no equipment, no helpers, and no curriculum – he would have to build the entire department from scratch. Expected to share a room with another faculty member, raise chickens and do other tasks he did not particularly care for, he was faced with students that were not that interested in learning what he had to teach them. But Carver had learned to take life as it came and make the most of it. It was never easy; his relationship with Booker T. was often strained, the latter trying to keep the institution from going broke, and the former more visionary than resources permitted. But they needed each other, and complemented each other, as iron sharpens iron, a fact George never fully realized till after Booker’s death.

Carver slowly got his students on track and began spinning a list of achievements that overflowed by the bushels. His classes did experiments with sweet potatoes, trying to increase crop yields. His all-time record was 266 bushels per acre, with the proper cultivation and fertilization. His abilities in agriculture seemed endless. He experimented with crop rotation and found ways for farmers to replenish the soil. When his list of useful products from common crops began to grow he started a ministry of help to poor farmers. He and his students put a classroom on a wagon and traveled from farm to farm teaching farmers how they could improve their yields.

Carver realized that cotton, a mainstay of southern farms, not only depleted the soil, but the devastating boll weevil that was slowly working its way east from Mexico and Texas at about 100 miles per year would wipe out the cotton crop economy. Peanuts and other legumes, he demonstrated, not only replenished the soil, but were extremely versatile and healthy. The threat of the boll weevil forced some farmers to take his advice and grow peanuts, but some became angry when they could not find a market for them, driving Carver to launch a series of amazing discoveries.

As he would tell the story later, he went out to pray as was his daily practice and asked God why he made the peanut. According to Carver, God told him to go into his lab and find out. In a Spirit-filled rush of discovery, Carver separated peanuts into their shells, skins, oils and meats and found all kinds of amazing properties and possibilities, discovering over 300 uses for the peanut from soap to malaria medicine.

But it wasn’t just peanuts. Carver invented 35 products from the velvet bean and 118 products from the sweet potato. From plant material Carver invented axle grease, bleach, chili sauce, ink, linoleum, meat tenderizer, metal polish, plastic, paint, synthetic rubber, and wood stain, to name only a few. George Washington Carver became the father of a new branch of applied science called agricultural chemistry or “chemurgy.” The extent of his discoveries in this field are breathtaking, and unlikely to be surpassed by any one person again.

Just a few of these products could have made him rich, but Carver made them available freely. As a servant of God, he felt that God should have the credit for putting all this richness into the plants He had made. Carver did not seek fame, but his work brought him world-wide renown, even a visit from Teddy Roosevelt.

Carver never made much money in his 40+ years at Tuskegee but gave generously from his meager assets. Driven by the needs of those he served there, he turned down a lucrative offer to work for Thomas Edison. As a popular speaker, projecting a visage of integrity with the rhetorical intensity characteristic of a preacher, Carver inspired the young to rise above their hardships, as he had done, and make their life count.

All who knew George Washington Carver were impressed by his spirituality. Carver would often rise at 4:00 in the morning and go into his favorite woods to pray. Each day he would ask, “Lord, what do you want me to do today?“ and then do it. The goodness of God and the richness of creation was often on his lips. He said, “I love to think of nature as an unlimited broadcasting station, through which God speaks to us every hour, if we will only tune in.”

Carver did not have a prejudicial bone in his body, although he was a target of racial bigotry on many occasions. He quietly demonstrated to the world that a man’s worth is not to be judged by the color of his skin, but the content of his character. And what character George Washington Carver had. He won the Roosevelt Medal in 1939, with the inscription, “To a scientist humbly seeking the guidance of God and a liberator to men of the white race as well as the black.”

Entering glory after a long and productive life, he was given the epitaph, “He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.”