As early as 2015, experts were raising biosecurity concerns about the genome-editing technology CRISPR. The FBI, the Pentagon, and the U.N.’s bioweapons office were warning that the most powerful use of gene-editing, aka “gene drive,” could become a tool of mass destruction in the hands of bioterrorists. Last year, James Clapper, director of National Intelligence, added gene-editing to a list of threats posed by weapons of mass destruction and proliferation because of the fear that development of CRISPR could have “far reaching economic and national security implications.”

As early as 2015, experts were raising biosecurity concerns about the genome-editing technology CRISPR. The FBI, the Pentagon, and the U.N.’s bioweapons office were warning that the most powerful use of gene-editing, aka “gene drive,” could become a tool of mass destruction in the hands of bioterrorists. Last year, James Clapper, director of National Intelligence, added gene-editing to a list of threats posed by weapons of mass destruction and proliferation because of the fear that development of CRISPR could have “far reaching economic and national security implications.”

Biotechnology is a “dual use” technology that proves that just because you can doesn’t mean you should. Everything we do has consequences. Biotechnology, more than any other domain, has great potential for human good, but in the wrong hands it could doom the human race. Daniel Gerstein, former under-secretary at the Department of Homeland Defense explained it best: “We are worried about people developing some sort of pathogen with robust capabilities, but we are also concerned about the chance of misutilization. We could have an accident occur with gene-editing that is catastrophic, since the genome is the very essence of life.”

Apparently real concerns didn’t slowed down progress on the development of this new technology because in July of this year, the first “known” attempt at creating genetically modified human embryos in the U.S. was carried out by a team of researchers in Portland, Oregon. Lead by Shoukhrat Mitalipov of Oregon Health and Science University, researchers changed the DNA of a large number of one-call embryos using CRISPR. Although none of the embryos were allowed to develop for more than a few days, the experiments were hailed as a milestone on what may prove to be an inevitable journey toward the birth of the first genetically modified humans.

Robert Gebelhoff, in an article at the Washington Post compared gene-editing to eugenics, “the science of improving people through controlled breeding.” But Scientists like the Nobel Laureate Joshua Lederberg and evolutionary biologist J.B.S. Haldane believe gene-editing, like eugenics, should be used by society to “guide human development by eliminating negative traits and encouraging desirable ones.” Considering that this technology is being pushed for the “greater good,” I am afraid that in the not so distant future, negative traits and desirable traits will be determined by a worldview that claims to act in the name of the public good under the mantle of scientific objectivity.

Nessan Bermingham, CEO of Intellia Therapeutics, sees gene-editing as the future because, after all, “wasn’t the point always to understand and control our own biology – to become masters over the processes that created us?”

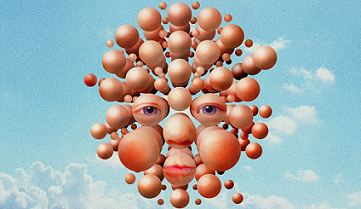

Playing God with human genetics! What could possibly go wrong?

If germ-line engineering becomes part of medical practice, it could lead to transformative changes with consequences to life spans, identity, and even economic output. It will also create ethical dilemmas and social challenges. More than likely, these “improvements” will only available to the richest of society and the political elite? But what else is new? An in vitro fertility procedure which already costs around $20,000 in the U.S. will soar with gene-editing, putting it far above that which the “peasants” can afford. But who needs those pesky peasants mucking up society in a world of designer babies and super humans?

Recommendations from the National Academy of Sciences would allow the technology to be used only to treat or prevent “serious disease or disabilities.” Does anyone truly believe that when perfected, gene-editing will be only used for the elimination of serious diseases and disabilities? How long before the jump to enhancing intellect, physic or psychological traits? How long before the creation of superior humans? We may play God, but we certainly don’t have the power to foresee all the consequences of assuming that role.

Perhaps the most horrifying example of playing God are the experiments carried out in three separate labs in the UK which allowed the creation of human-animal hybrids having physical features of animals but with the cognitive power and consciousness of a human. These hybrids were made possible by technologies like CRISPR and human stem cell manipulations and fertilizing an animal egg with human sperm. A lot of organizations have implied that these procedures are for medical research, but scientists have argued that nothing good can come out of developing new species that have horrifyingly human like features previously only confided in science fiction.

Creating human-animal chimeras raises a number of ethical questions. At what point would this creation be considered human or what rights, if any, should it have? David Magnus, director of the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics at Stanford University said in 2005 that the real worry is whether or not chimeras will be put to uses that are problematic, risky, or dangerous. For example, an experiment that would raise concerns, he said, is genetically engineering mice to produce human sperm and eggs, then doing in vitro fertilization to produce a child whose parents are a pair of mice. While that may sound far-fetched – is it really?

“We hear constantly how complex everything is. What makes us think we can tinker with this incredible biological reservoir of information without making some incredible blunder from which there is no turning back?” Dr. Ray Bohlin