According to conventional wisdom, one of the prerequisites for a civilized society is a system of government enforced licensing of numerous occupations to assure specific standards. Government claims that the safety and well-being of consumers impels it to enact these laws, which ensure the superior quality of various products and services purchased by consumers, as compared to what would be available in the absence of such laws.

According to conventional wisdom, one of the prerequisites for a civilized society is a system of government enforced licensing of numerous occupations to assure specific standards. Government claims that the safety and well-being of consumers impels it to enact these laws, which ensure the superior quality of various products and services purchased by consumers, as compared to what would be available in the absence of such laws.

Unfortunately, these laws also create unemployment and underemployment which disproportionately affects the poor, while producing higher incomes for those employed in the protected occupations, higher prices for consumers , with fewer options available to consumers, thus moving us further away from the government’s stated goal.

If there could be only one occupation subject to legal licensing, a majority of the public would likely say it should be doctors. However, before the government’s licensure intervention, our ancestors had a different view. In Canadian Medicine, A Study In Restricted Entry (p 125), Ronald Hamowy wrote that despite the actions to suppress unregistered doctors, the public, especially the poor, continued to use their services, finding them no less competent than those who held a license and less expensive to see. The profession’s attempt to suppress these doctors was not motivated out of a selfless interest in improving the quality of medical care offered the public, but out of a desire to lessen competition, which would in turn increase their own incomes.

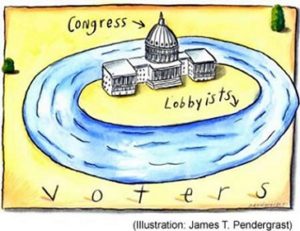

As it is in the medical field, so it is with virtually every occupation subject to licensing. Various occupational associations, not consumers, lobby the government to enact new licensing laws or add new restrictions to the current laws to line their own pockets. From eyebrow threading, to dog-sitting , to florists, to strippers, to hair braiding, to mowing lawns, there are numerous occupations where licensing serves no other purpose than to provide revenue for the government and benefits for entrenched interests, all at the expense of consumers and job-seekers.

Data compiled by the Institute for Justice shows just how far states have overreached in regulating professions. The report, “License to Work,” shows that 1 in 4 jobs are now restricted by licensing requirements, and that these onerous rules generally do nothing to improve service or protect people. As a matter of fact, as licensing becomes more and more widespread, more and more industries now feel the need to lobby for licensing of their profession lest they be perceived as insignificant.

Take for instance the American Society of Interior Designers who spent over 3 decades lobbying state legislatures to institute licensure requirements. Three states and D.C. gave and adopted regulations and a number of others agreed to titling requirements that restrict the job title an “uncertified” interior designers can use.

The licensure requirement imposes expensive and time consuming requirements for accreditation that prevent many talented new workers from entering the industry. As a result, the labor supply is smaller and members of the American Society of Interior Designers can charge more.

From 2005-2013, dentistry lobbyists succeeded in shutting down teeth whitening businesses in at least 30 states, arguing that they should be restricted to only dentists, citing “health concerns.” Teeth whitening businesses generally offer the same products that could be purchased over the counter, and practitioners rarely make physical contact with their patients. But the dentistry lobby successfully grabbed a line of business from its competitors.

In 1944, the American Dietetic Association president called for licensing rules for nutritionists because “there is a need for improving the status of dietitians.” The American Music Therapy Association used the same logic in 2005 when it called for licensing requirements “to achieve state recognition for the music therapy.”

Most licenses are not easy to obtain. A study of 102 of the most significant licensure requirements showed that the average cost to obtain them is $267 in fees, an exam, and a year of education and experience. And, there is little or no correlation in cost and time to the risk of the occupation.

Cosmetologist training, for example, takes over 12 times longer than training to be an Emergency Medical Technician. In some states, barbers or hair stylists must receive at least an associate (two year) college degree, despite the fact that even the trickiest tasks they perform, dealing with treatments or chemicals, for example, can be mastered through on-the-job training. Until recently, becoming a master plumber in Illinois took longer than becoming a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons. In New York City, a “master plumber” must have 20 years of experience as a “journeyman” under a master plumber in New York City. Ten years of experience in Philadelphia or Akron do not count.

When government sets the standards for quality, the standards are more likely to be dictated by political pressure than by the need to protect consumers.

Sources: The Problem with Government Licensing Schemes by Lee Friday, Mises Institute ; How Licensing Laws Protect Special Interests at the Expense of Everyone Else, by Timothy Kilcullen, The Daily Signal; Does Occupational Licensing Protect Consumers? by John Hood, the Foundation for Economic Education