Love of the Rebel flag is authentic, deep-seated, and long-lasting. Hatred of the flag is a recently invented political weapon.

Love of the Rebel flag is authentic, deep-seated, and long-lasting. Hatred of the flag is a recently invented political weapon.

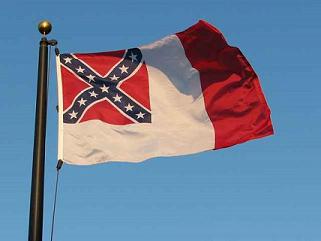

Historically, the Battle “Rebel” Flag, with its familiar Cross of St. Andrew, was designed to represent the historic Celtic and Christian origin of many Southerners. It was not the national flag of the Confederacy that flew over slavery, but rather, a flag carried into battle by soldiers, 90% of which had never owned a slave nor were fighting to protect the rights of wealthy Democrat slaveowners.

Public display of the flag has been commonplace throughout the centuries and not just in the South. The flag appeared as a symbol of liberation at the fall of the Berlin Wall and the freedom of the Baltic countries and as a protest against the European Union.

FDR nor Eisenhower fled in terror from being photographed with it. The great Toscanini played a rousing version of “Dixie” when he toured the U.S. during WWII and Korea, and I expect Vietnam. The flag also appeared in front of Marine tents near the front, was emblazoned on fighter planes and flown at the conquest of Iwo Jima, that is before the US armed forces became historically ignorant and gender-neutral politically correct institutions.

The far-left charge that the flag represents “treason against the Federal government.” Showing their ignorance of history and the Constitution, they neglect to mention that the right of secession and the actions of the Southern states, December 1860-May 1861, could be justified under the US Constitution.

One of the best summaries of the prevalent Constitutional theory was made by black scholar, professor, and prolific author Dr. Walter Williams. I quote from one his recent columns: During the 1787 Constitutional Convention, a proposal was made that would allow the federal government to suppress a seceding state. James Madison rejected it, saying, ‘A union of the states containing such an ingredient seemed to provide for its own destruction. The use of force against a state would look more like a declaration of war than an infliction of punishment and would probably be considered by the party attacked as a dissolution of all previous compacts by which it might be bound.’

In fact, the ratification documents of Virginia, New York and Rhode Island explicitly said they held the right to resume powers delegated should the federal government become abusive of those powers. The Constitution never would have been ratified if states thought they could not regain their sovereignty.

The Supreme Court affirmed this view. In The Bank of Augusta v. Earl (1839), the Court wrote in an 8-1 decision that “The States…are distinct separate sovereignties, except so far as they have parted with some of the attributes of sovereignty by the Constitution. They continue to be nations, with all their rights, and under all their national obligations, and with all the rights of nations in every particular; except in the surrender by each to the common purposes and object of the Union, under the Constitution. The rights of each State, when not so yielded up, remain absolute.”

So, to boil something as complex as the Civil War down to nothing but slavery is simplistic and wrong. To say the least, the causes and consequences of the War were varied and complicated. There was the Morrill Tariff that created a 47% tax targeting the Southern ports; there were radical abolitionists who were calling for the death of all southern slave owners and the one radical, John Brown, who tried to make good on that promise; and then there was Lincoln’s own admission at the outset that the war was not in any way about freeing the slaves? He said in his first inaugural that he would go to war with the South for two reasons only: 1) to re-secure federal property and 2) to collect federal taxes.

Lincoln wrote to Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, on August 22, 1862, “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery….”

The Emancipation Proclamation was a desperate political ploy by Lincoln to churn up sagging support for a war that appeared stale-mated at the time. Indeed, Honest Abe had previously called for sending blacks back to Africa and the enforcement of laws that made Jim Crow look benign. He knew fully well that “freeing the slaves” had no support in the North and was not the reason for the conflict. His Proclamation applied only to Southern states in which the Federal government had no authority. States that the Union controlled such as Maryland and Kentucky, both slave states, were exempt.

Secession does not necessitate war. It was only when the Southern states refused to pay his beloved Morrill Tariff at Southern ports, monies that supplied a major portion of federal revenue, that Lincoln kept his promise of invasion and bloodshed against the South.

Today we live in a country characterized by what historian Thomas Fleming says afflicted the nation in 1860 – “a disease in the public mind,” a collective madness, lacking in both reflection and prudential understanding of our history.

And that madness is all around us. The Rebel Flag has been removed from the public square. We are seeing the attempted obliteration of all southern names and history from our lexicon. Monuments of Southern presidents and supporters are being defaced and removed up to and including the statute of Abraham Lincoln. Cemeteries of confederate veterans are being destroyed. The left is calling for the renaming of all schools, colleges, parks and military bases named after our southern ancestors. What next? Are we to see Mount Rushmore blown up? Why stop there?

It is a slippery slope, but an incline that in fact represents a not-so-hidden agenda, a cultural Marxism, that includes the remaking of what remains of our nation. And, since it is the South that has been most resistant to such impositions and radicalization, it is the South, the historic South, which enters the cross hairs as the most tempting target.

“If ever the free institutions of America are destroyed that event may be attributed to the unlimited authority of the majority, which may at some future time urge the minorities to desperation, and oblige them to have recourse to physical force….[l]t will have been brought about by despotism [of the majority].” Alexis de Tocqueville, 1835

Source: A Sickness in the Public Mind, by Boyd Cathey, Ph.D; Our Noble Banner, by Clyde Wilson, Professor Emeritus of History, USC; The Civil War; The Mythmanagement of History, by Ludwell H. Johnson, Emeritus Professor of History, College of William and Mary