We are once again mired in a frantic debate about the rights of gun owners. And as usual the left is determined to tag law abiding gun owners as enablers of mass murder.

We are once again mired in a frantic debate about the rights of gun owners. And as usual the left is determined to tag law abiding gun owners as enablers of mass murder.

Let’s be clear. The Second Amendment is not about assault weapons, hunting, or sport shooting. It is about something more fundamental that reaches to the heart of constitutional principles. A favorite refrain of thoughtful political writers during America’s founding era held that a frequent recurrence to first principles was an indispensable means of preserving free government—and so it is.

The Whole People Are the Militia. The Second Amendment reads: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” The immediate impetus for the amendment has never been in dispute. Many of the revolutionary generation believed standing armies were dangerous to liberty while Militias, made up of citizen-soldiers, were more suitable to the character of a Republic style government. Expressing a widely held view, Elbridge Gerry remarked in the debate over the first militia bill in 1789 that “whenever Governments mean to invade the rights and liberties of the people, they always attempt to destroy the militia.”

The Second Amendment is unique among the amendments in that it contains a preface explaining the reason for its inclusion: Militias are necessary for the security of a free state. We cannot read the words “free State” here as a reference to the several states that make up the Union. The frequent use of the phrase “free State” in the founding era makes it abundantly clear that it means a non-tyrannical or non-despotic state. Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the majority in the case of District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), rightly remarked that the term and its “close variations” were “terms of art in 18th-century political discourse, meaning a free country or free polity.” The principal constitutional debate leading up to the Heller decision was about whether the right to “keep and bear arms” was an individual right or a collective right conditioned upon service in the militia. As a general matter, of course, the idea of collective rights was unknown to the Framers of the Constitution, and this consideration alone should have been decisive. We have James Madison’s own testimony that the provisions of the Bill of Rights “relate [first] . . . to private rights.”

The notion of collective rights is wholly the invention of the Progressive founders of the administrative state, who were engaged in a self-conscious effort to supplant the principles of limited government embodied in the Constitution. For these Progressives, what Madison and other Founders called the “rights of human nature” were merely a delusion characteristic of the 18th century. Science, they say, has proven that there is no permanent human nature—that there are only evolving social conditions. As a result, they regarded what the Founders called the “rights of human nature” as an enemy of collective welfare, which should always take precedence over the rights of individuals.

For Progressives then and now, the welfare of the people, not liberty, was and is the primary object of government, and government should always be in the hands of experts. This is the real origin of today’s gun control hysteria—the idea that professional police forces and the military have rendered the armed citizen superfluous; that no individual should be responsible for the defense of himself and his family, but should leave it to the experts. The idea of individual responsibilities, along with that of individual rights, is in fact incompatible with the Progressive vision of the common welfare.

This way of thinking was wholly alien to America’s founding generation, for whom government existed for the purpose of securing individual rights. And it was always understood that a necessary component of every such right was a correspondent responsibility. Madison frequently stated that all “just and free government” is derived from social compact, the idea embodied in the Declaration of Independence, which notes that the “just powers” of government are derived “from the consent of the governed.”

Social compact, wrote Madison, “contemplates a certain number of individuals as meeting and agreeing to form one political society, in order that the rights, the safety, and the interests of each may be under the safeguard of the whole.” The rights to be protected by the political society are not created by government, they exist by nature, although governments are necessary to secure them. Thus political society exists to secure the equal protection of the equal rights of all who consent to be governed. This is the original understanding of what we know today as “equal protection of the laws”—the equal protection of equal rights.

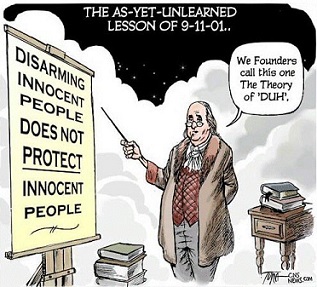

Each person who consents to become a member of civil society thus enjoys the equal protection of his own rights, while at the same time incurring the obligation to protect the rights of his fellow citizens. In the first instance, then, the people are a militia, formed for the mutual protection of equal rights. This makes it impossible to mistake both the meaning and the vital importance of the Second Amendment: The whole people are the militia, and disarming the people dissolves their moral and political existence.

For the moment, Second Amendment rights seem safe, but as Abraham Lincoln once remarked, “Whoever molds public sentiment, goes deeper than he who enacts statutes, or pronounces judicial decisions.” Shaping and informing public sentiments, [opinion] is political work, and thus it is to politics that we must ultimately resort. But at this point. while we might see some “tinkering” with current gun laws regulating back ground checks, I doubt that any major legislation to ban guns will make to the president’s desk.

Can a president go against the tide of public opinion? Of course he can – Obama taught us that. The President’s power to act through executive orders is as extensive as it is ill-defined. Congress routinely delegates power to executive branch agencies, and the courts accord great deference to agency rule-making powers, often interpreting ambiguous legislative language or even legislative silence as a delegation of power to the executive. Such delegation provokes fundamental questions concerning the separation of powers and the rule of law. Many have argued that it is the price we have to pay for the modern administrative state—that the separation of powers and the rule of law have been rendered superfluous by the development of this state. Some of the boldest proponents of this view confidently.

The Gun Control Act of 1968 gives the President the discretion to ban guns he deems not suitable for sporting purposes. Would the President be bold enough or reckless enough to issue an executive order banning the domestic manufacture and sale of AR-15’s or other guns he might ill-define as an assault weapon? Might he argue that these weapons have no possible civilian use and should be restricted to the military, and that his power as commander-in-chief authorizes him so to act? And what criteria would he use to define what an assault weapon is?

Congress could pass legislation to defeat such an executive order; but could a divided Congress muster the votes? And even if they did would the president sign it? More than likely individuals would have to resort to the courts; but as of yet, we have had no ruling that assault weapons are not one of the exceptions that can be banned or regulated under Heller. We could make the case that these so-called assault rifles are useful for self-defense and home defense; but could we make the case that they are essential? Would the courts hold that the government had to demonstrate a compelling interest for a ban on so-called assault rifles, as it almost certainly would have to do if handguns were at issue?

Are these simply wild speculations? Perhaps—probably! But they are part of the duty we have as citizens to engage in a frequent recurrence to first principles.

Source: The Second Amendment as an Expression of First Principles by Edward Erler, professor of political science, California State University, San Bernardino, which can be read in full at this link.